The automotive industry - particularly in Europe - is undergoing the greatest transformation in its history. It is facing unprecedented regulatory pressure to abandon petroleum and shift to all-electric vehicles.

This transition is complex, full of obstacles, and riddled with uncertainty: will electric cars ultimately win over the market? If so, how quickly? Should the development of internal combustion engines continue as a “Plan B”? Should we bet on plug-in hybrids? On conventional hybrids? On range extenders for electric vehicles?

Ultimately, the market will determine what sells, and voters will shape regulatory policies.

To reduce the climate impact of automobiles, several scenarios are possible. The respective roles that electric traction, internal combustion engines, and alternative fuels will play are not yet clear.

Given these uncertainties, phasing out the internal combustion engine too quickly is risky: it still dominates the market because it meets users’ expectations. It remains economically accessible, highly valued by consumers, and is the only short- and medium-term solution in many regions of the world for powering vehicles.

Nevertheless, electric vehicles are progressing. They benefit from intense research and development efforts and strong government support. However, they remain more expensive to purchase than their combustion-engine counterparts - by +30% to +45% in Europe - which limits their market. Moreover, they depreciate rapidly: around -45% to –60% over three years (source: Rouleur Électrique), compared with -35% to -40% for combustion vehicles.

Combined with the higher purchase price, this rapid depreciation represents a significant financial loss that is not offset by the lower cost of home charging. The reasons include: the fast pace of technological improvement from one EV generation to the next, which accelerates obsolescence; concerns about battery durability; and fears of complex, high-cost repairs requiring highly specialized labor.

Other barriers to EV adoption remain: lack of access to home charging for people who do not live in single-family houses, and anxiety related to limited range and long charging times. Cultural factors also play a role: the pleasure of driving a combustion vehicle, the sense of freedom it provides, fear of the unknown, and in some cases mistrust toward a technology perceived as politically imposed without prior consultation.

In Europe in 2024, despite purchase penalties and fuel taxes amounting to roughly €6/100 km imposed on combustion vehicles, and despite purchase subsidies and an electricity tax of only €1.5/100 km benefiting electric vehicles (for home charging), EVs accounted for only 13.6% of sales in a car market down nearly 17.2% compared with 2019. The same absolute number of EVs sold in 2019 would have represented 11.3% of the market.

Nothing seems to deter lawmakers and political authorities from pushing users toward electric cars. France - a world champion of taxation - has even invented the “incentive annual tax”: companies that do not purchase enough electric vehicles (BEVs, PHEVs emitting less than 50 g CO2/km, or hydrogen vehicles) must pay a penalty for the vehicles they did not buy.

For now, electric cars are not responding to a groundswell of public demand. Their market is still driven by incentives, coercive measures, constraints, and significant pressure on taxpayers and public finances. It is clear that the conditions for the mass adoption of electric vehicles are not yet in place.

Burdened by constraints, standards, regulations, and heavy investments in electrification - costs partly absorbed by combustion vehicles - the automotive sector has become expensive. Too expensive? The average price of cars rose by 24% between 2020 and 2024 across all powertrains. As a result, the market is contracting sharply under the weight of declining purchasing power. The vehicle fleet is aging, which is not beneficial for the environment.

Cars are becoming luxury goods, packed with complex technologies imposed by an unprecedented wave of regulations. These technologies lead to costly, difficult-to-resolve breakdowns. This pushes drivers toward used cars from the 2010s, which are simpler, more reliable, and cheaper to repair. In France, small used cars - historically popular among the general public - are in high demand and often sell for +15% to +20% above their Argus valuation: production of such vehicles dropped drastically starting in 2020, made nearly impossible by overwhelming regulatory requirements.

Another barrier to EV adoption is their actual environmental benefit, which is a source of concern. For now, electric cars are misleadingly labeled “zero emission” by lawmakers. This does not reflect reality. With Europe’s low-carbon electricity mix, a battery electric vehicle emits about half as much CO2 as an equivalent combustion vehicle over its full life cycle, from cradle to grave. That is significant - but it is not “zero”:

Average carbon footprint of a car sold in 2025 by country and electricity-mix decarbonization – D-segment – 200,000 km | gCO2e/km

(Source: Carbone 4 [https://www.carbone4.com/analyse-faq-voiture-electrique])

In this respect, no vehicle meets the “100% CO2 reduction” required by European legislation for 2035 - not even a bicycle. Worse, over 200,000 km, a large electric SUV “made in China” may in many cases emit more CO2 per kilometer than a small combustion car. Wealthy consumers will thus be able to buy a large, high-emitting electric SUV, while lower-income households will be prevented from purchasing a smaller, less polluting combustion vehicle.

But there is some reassurance: this exceptional “zero-emission” designation will not last forever. Sooner or later, regulations will account for emissions over the entire life cycle of vehicles - from manufacturing to recycling, including their use phase. The same will happen for combustion cars, whose emissions are currently regulated only “from tank to wheel.” This is absurd: it is “actual” emissions, not “regulatory” emissions, that affect the climate and the environment.

Once these “actual” emissions are taken into account, the evolution of powertrains - and above all the evolution of the origin of the energy they consume - will make it possible to assess their true environmental footprint. This assessment will include CO2 emissions as well as impacts on water, air, and soil pollution, and the direct and indirect harm caused to human populations and biodiversity.

In principle, electric cars will become cheaper, their range will increase, charging infrastructure will become denser, and their environmental impact will decrease thanks to more eco-friendly battery chemistries.

All of this is “in principle,” because battery prices could also rise due to dwindling mineral resources, restrictions that limit access to them, a monopoly position in Asia that could encourage price increases, or a battery industry that is less over-capacitated than it is today in China.

In parallel, the efficiency of internal combustion engines will continue to improve through technical progress, and the fuels they use will become increasingly climate-friendly.

As a result, the environmental gap between electric and combustion vehicles may shrink or even disappear. More importantly, each strategy will be able to prevail depending on regions, markets, and use cases. India, for example, will see its vehicle fleet explode by 2050. For that country, the priority is to decarbonize electricity production before introducing electric cars, which for now emit more CO2 there than their combustion equivalents (see previous graph).

In such a vast and complex world, both combustion and electric technologies will provide solutions. This is why they should complement rather than oppose each other - whether within a single vehicle or across different vehicles depending on usage requirements or country of registration.

Open-mindedness, pragmatism, technological neutrality, and caution will yield far better results than rigid, dogmatic stances based on incomplete or unrealistic impact assessments.

Approximately 3 billion internal combustion engines are currently in service worldwide across all sectors. Of the 1.45 billion cars on the road globally, 97% are powered by combustion engines. The same was true in 2024 for 87% of new cars sold worldwide (source: AlixPartners).

In Europe, an electric car reduces CO2 emissions by roughly 50% compared with an equivalent combustion vehicle. This is largely due to the low-carbon nature of European electricity. This reduction could reach 70% by 2040 if combustion engines did not evolve proportionally. However, the development of electric vehicles will likely take longer than initially anticipated. Moreover, if EV adoption remains limited to wealthy countries, its overall climate benefit will remain modest.

Indeed, the rapid economic growth of densely populated regions such as Africa, South Asia (India), the Middle East, and South America will create a serious greenhouse-gas emissions challenge. As Europe did in the early 20th century, these regions will rely on the cheapest and most accessible energy resources to develop. India, for instance, still produces more than 70% of its electricity from coal. As a result, the consumption of fossil fuels continues to rise. In August 2025, global oil production reached a record 106.9 million barrels per day (IEA). Coal and gas continue to grow as well.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has ultimately revised its forecasts upward for global oil and gas consumption: the demand peak, initially expected before the end of the decade, has now been pushed back to 2050, at which point demand would reach 114 million barrels per day.

Efforts to combat climate change can only be effective if all countries - including developing ones - participate. Yet not all nations have the same resources or the same energy infrastructures.

The Risk of a European All-Electric Island:

In the name of the “Green Deal,” Europe is among the few regions in the world seeking to ban the internal combustion engine in favor of an all-electric paradigm. In doing so, Europe is sacrificing its automotive industry to the benefit of China. It is an industrial and economic earthquake. This strategy is likely to produce the opposite of what is intended, inflicting irreversible damage on European prosperity, according to the following sequence:

Ban on combustion engines à Loss of European automotive sovereignty à Collapse of European industry à Decline in living standards à Social tensions à Rise of populism à Reversal of the Green Deal.

Producing 100% European electric cars? The game is lost in advance against China: two-thirds of electric cars are sold in China, which produces 80% of the world’s batteries, 85% of cathode active materials, and more than 90% of anodes. China files more patents in electric traction than any other country. It controls most of the extraction and refining of critical metals, which EVs require in very large quantities: nickel, cobalt, manganese, copper, lithium.

With massive government support for electric mobility (around USD 250 billion since 2009), labor costs three to seven times lower, near-monopolistic control of the value chain, a technological lead measured in decades, industrial capacity on an extraordinary scale amortizable over a huge domestic market, a Chinese battery will always remain 30–40% cheaper than its European counterpart.

This will be all the more true given that China has significant overcapacity in battery production. It will seek to capture foreign markets by any means necessary. To achieve this, it will lower prices as much as needed to dominate.

After a ruinous transition period for public finances and Western automakers, the latter will have no choice but to equip their electric vehicles with Chinese batteries in order to maintain a semblance of competitiveness. In doing so, they will transfer between 30% and 50% of their vehicles’ value to Chinese companies. By abandoning their expertise in combustion engines, they will write off industrial know-how and assets representing more than a century of uninterrupted effort. As Luc Chatel, president of the French Automotive Platform, notes: this is a genuine case of “industrial self-sabotage.”

At the end of an unequal battle, most European car manufacturers will disappear, just as most European producers of solar panels, wind turbines, or even T-shirts have. Exhausted, their factories will be sold to Chinese buyers for a symbolic one euro, with the sale justified by the preservation of a handful of jobs. China will then no longer need to worry about tariffs, since it will be operating within Europe - and Europeans will be its employees.

What will we, Europeans, gain from this?

The situation is all the more absurd given that in 2024, China exported 5.86 million vehicles (passenger cars + light commercial vehicles), of which 987,000 were fully electric cars (BEVs), 313,000 were plug-in hybrids, and all the rest were combustion vehicles. In 2024, 83% of Chinese vehicle exports therefore had a combustion engine. A pragmatic stance that contrasts sharply with Europe’s dogmatic approach.

With the internal combustion engine, we can take a more “global” approach to the climate challenge:

There is indeed an alternative to the “all-electric approach, whatever the cost to Europeans.” By taking this path, Europe could leverage its expertise and capabilities, and regain global leadership.

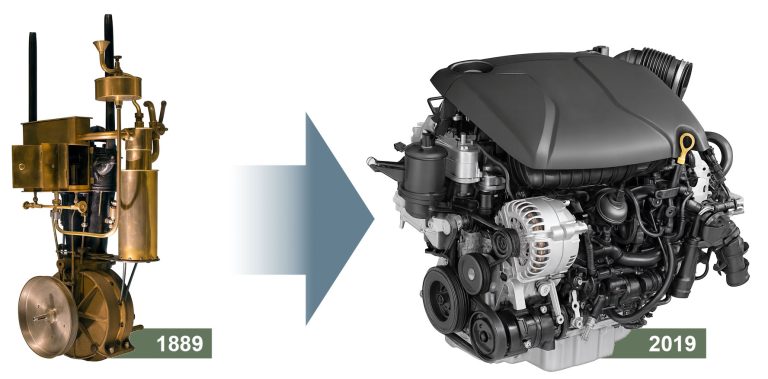

The idea would be to make the internal combustion engine - the result of 130 years of R&D - a cornerstone of the ecological transition on a global scale. This strategy would be far more effective in protecting the climate. It would consist of further improving the efficiency of combustion engines for the benefit of the entire planet, combining them with electric systems in a targeted way, and drastically reducing the environmental impact of the fuels they consume.

With this strategy, the internal combustion engine would no longer be a liability but an asset: it is favored by the market worldwide and benefits from massive global scale. Every improvement made to it has a large environmental impact. For example, if in 2024 the fuel consumption of all new combustion cars sold worldwide had been reduced by 10%, the average CO2 emissions of new cars would have been 28% lower than with the 13% share of fully electric vehicles sold that same year.

This approach is all the more relevant because the dominant position of the internal combustion engine is likely to endure, as it continues to meet user expectations in nearly all markets around the globe: a price compatible with people’s purchasing power without public subsidies, great versatility, and minimal usage constraints. If electric cars met those same expectations, it would not be necessary to subsidize them, nor to discourage by any means the purchase of combustion vehicles.

For more than 100 years, the internal combustion engine - despite being complex, heavy, noisy, and polluting - has supplanted the electric motor, which is simpler, lighter, quieter, and cleaner. In 1900, most automobiles circulating in American city centers were electric, and battery-powered cars made up one third of the national fleet.

What explains this historic reversal? At equal weight, including the tank, gasoline contains roughly 70 times more energy than a packaged automotive battery: about 11,000 Wh/kg for gasoline versus 150 Wh/kg for batteries. Another advantage is that a gasoline tank can be refilled in two minutes with a low-cost energy source that is naturally abundant, easy to store, transport, and distribute.

But times are changing: petroleum is a finite resource whose depletion must be anticipated decades in advance, and its combustion creates serious environmental problems.

Ensuring long-term mobility therefore requires a massive shift toward electricity, which can be produced from a much wider range of primary energy sources than petroleum alone: coal, gas, uranium, wind, solar, hydro, biomass.

However, moving away from an all-petroleum system does not mean giving up hydrocarbons (gasoline, diesel), whose exceptional energy density and usage flexibility will remain irreplaceable for a long time as a means of storing energy. Exiting petroleum dependence cannot be done in ten years: we rely on oil for a wide range of reasons that go far beyond the automobile alone.

This is why phasing out the internal combustion engine prematurely makes no sense:

Short trips – the supremacy of electric vehicles:

It is not relevant to assign short trips to a combustion engine. Every restart is polluting and energy-intensive. Moreover, short trips and urban driving often go hand in hand, and the efficiency of a combustion engine is poor at the very low power levels used in city driving.

In contrast, the efficiency of an electric drivetrain remains high at low power. In urban driving, braking is frequent. Electric vehicles make rational use of energy through regeneration and emit virtually no pollutants.

Long trips – the supremacy of the internal combustion engine:

I It is not relevant to assign long-distance travel to electrochemical batteries. Their energy density is so low that even with 500 to 600 kg of batteries - and a total vehicle weight 30% to 40% higher than that of an equivalent combustion car - range remains mediocre and the vehicle expensive to purchase.

Practical range is usually measured between 20% charge, below which it is not recommended to go in order to preserve battery life, and 80%, above which charging becomes slow. In this case, only about 60% of the battery’s capacity is typically usable on long trips, resulting at best in around 250 km of range for a car equipped with an 80 kWh battery.

Charging electrochemical batteries remains slow, even at supposedly “high-power” charging stations, whose dense deployment is costly for society: hundreds of billions of euros to equip Europe.

By contrast, it is on roads and highways that the efficiency of the internal combustion engine is at its highest. The energy density of the hydrocarbons it uses provides up to 1,000 km of range or more with under 50 kg of gasoline on board, with refueling completed in 2 to 3 minutes at service stations available worldwide.

Clearly, electric vehicles are perfectly suited to short trips and urban use, while combustion engines excel over long distances.

To understand this, one only needs to compare electrochemical batteries with liquid hydrocarbons, which in the future may be synthesized from low-carbon electricity of nuclear or renewable origin (e-fuels).

Energy density:

Including the fuel tank, gasoline indeed has a mass energy density (kWh/kg) roughly 70 times higher than that of an automotive lithium-ion battery.

For the same driving range, and taking into account average efficiencies (≈25% for a combustion engine versus ≈70% for an electric drivetrain), a vehicle must carry about 25 times more battery mass than gasoline (0.25 ÷ 0.7 × 70 = 25).

Thus, to travel the same distance, 1 kg of gasoline replaces 25 kg of batteries. As a result, despite carrying several hundred kilograms of batteries, electric vehicles offer significantly lower driving range than their combustion equivalents.

Let’s compare two concrete cases:

Volkswagen ID.3 (electric):

Volkswagen Golf (gasoline):

If this Golf carried 516 kg of fuel, like the ID.3 carries in batteries (≈630 L of gasoline), its range would reach 10,200 km. At 12,000 km per year (French average), refueling would be needed only every 10 months

Refueling / Charging:

A fuel pump transfers energy into the tank of a gasoline Golf at a minimum power of 22.4 megawatts (0.7 L of gasoline per second × 32 MJ/L). This is 160 times more than the power delivered by a fast-charging station to an electric ID.3 equipped with a 79-kWh lithium-ion battery.

Because the ID.3 uses secondary energy (the transformation of primary energy occurs in the power plant), it makes better use of the energy delivered at the charging point than the combustion car, which converts primary energy (fuel) on board.

Even taking this into account, it still takes more than 50 times longer to “recharge” 1 km of driving range in the electric ID.3 than in the gasoline Golf.

The tables below show the difference in effective charging/refueling power between an electric car and its combustion equivalent:

Our environmental problem does not come from the internal combustion engine but from the petroleum it consumes.

Petroleum is abundant: at the current extraction rate, reserves will last at least another 50 years. It is inexpensive, easy to distribute, transport, and store. Its energy density is extraordinary - about 12 kWh per kilogram. At $70 per 159-liter barrel, of which 80% becomes fuels with an average density of 850 g/L, the “petroleum kWh” costs roughly 70 / (159 × 0.8 × 0.85 × 12) = 5.4 cents. On top of this unbeatable price, petroleum also yields - essentially for free - numerous products indispensable to industry.

We are so dependent on petroleum that if we stopped consuming it, the entire world economy would collapse. This dependence extends far beyond transportation: many products rely on petroleum, including those required to manufacture wind turbines, solar panels, and electric cars - the very technologies meant to free us from petroleum. The paradox is obvious.

Our dependence on petroleum spans organic chemistry, synthetic rubbers and fibers (polyester, nylon, acrylic), glues, paints, solvents, lubricants, food packaging, agricultural inputs, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and excipients. Bitumen - which covers more than 90% of the world’s roads - is 100% petroleum-derived. Between 50% and 60% of the mass of a tire also comes from petroleum.

For now, the sustainability of our lifestyles depends on the remaining fossil resources that can still be extracted. However, their impact on the climate will not allow us to consume them to the end. We are trapped.

It is therefore virtuous to do everything possible to free automobiles from their dependence on petroleum. This objective attracts intense attention and fuels passionate debate. However, achieving it requires that our entire industrial system also free itself from petroleum - including ships, aircraft, and trucks, which are far more difficult to electrify than cars.

Indeed, moving away from petroleum means reducing consumption proportionally across all sectors. When a 159-liter barrel of crude oil is distilled, between 65 and 70 liters of gasoline are produced - almost half. More than 80% of this gasoline is consumed by cars. If cars stop consuming gasoline, then other sectors must also stop using petroleum; otherwise, that gasoline will have to be converted into something else.

Converting this “stranded gasoline” into other products is technically possible. However, the energy and economic cost of such conversion is high and results in additional greenhouse-gas emissions. Because this conversion is complex and expensive, unconsumed gasoline in Europe will very likely be consumed elsewhere. It will be burned in cars in other parts of the world. The climate benefit will be zero.

Other effects can be expected: if Western countries significantly reduce their petroleum consumption, the resulting drop in demand will lower the price of crude oil. This will make oil more accessible to emerging economies, which will consume more of it, develop more rapidly, and put more combustion vehicles on the road.

Given the persistent relationship between GDP and oil consumption, this shift of petroleum use from Western nations to emerging countries will be accompanied by a transfer of wealth, a shrinking of the Western vehicle fleet, and a growth of the fleet in emerging economies. These densely populated regions have an immense appetite for mobility: the global vehicle fleet will expand dramatically - to the detriment of the climate - rising from 1.45 billion today to 2.2 billion in 2050, according to projections by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

In 2021, the EIA estimated that by 2050, 31% of cars on the road worldwide would be fully electric or plug-in hybrids. Under this assumption, there would be more internal combustion engines in service in 2050 than in 2025 - that is, 2.2 × 0.69 = 1.52 billion - not including the combustion engines inside hybrid vehicles.

Since by that time all cars in the world will have been replaced, and still following this scenario, a minimum of 2.2 billion cars would need to be produced over 25 years, or 88 million per year. Given that the lifespan of a car is shorter than 25 years, annual production would more realistically be around 100 million vehicles per year between now and 2050, of which approximately 70% could still be equipped with combustion engines.

This is why developing high-efficiency combustion vehicles is essential. On a global scale, they will dominate the market for many more decades, often combined with electric systems (hybrids). This will remain the case until the unavoidable transition toward non-fossil energy sources is achieved.

During this transition, producing high-efficiency combustion engines will yield a net reduction in global CO2 emissions. This strategy will also open new pathways through the use of carbon-neutral fuels, combined with electrification, gradually accompanying the phase-out of petroleum.

The internal combustion engine will continue to be favored by the market - and will be irreplaceable in many regions of the world - as long as electricity is not available everywhere in sufficient quantities, affordable to store on board, offering high energy density and short charging time.

This is why reducing the carbon footprint of automobiles requires:

Because greenhouse gases have no borders, only low-carbon technologies that can be widely deployed at a global scale will be effective in combating climate change. To succeed, low-carbon vehicles must remain attractive, affordable, versatile, durable, and easy to repair - qualities that internal combustion vehicles naturally provide.

Without these qualities, low-carbon vehicles will fail to achieve the expected market success, their climate impact will remain limited, they will not be profitable for manufacturers, and they will drain public finances if imposed through top-down policies disconnected from market realities. The resulting economic and social consequences would be severe:

The internal combustion engine is therefore one of the resources that must be prioritized to achieve the best economic, environmental, and social balance. This is why, as an alternative to the “all-electric at any cost” approach, technological neutrality is essential to meet all use cases and all markets. Many leaders in the automotive industry - particularly in Europe - are calling for such neutrality.

For the automotive transition to gain public support and have a strong impact on environmental and energy challenges, it will be necessary to leverage the specific strengths of the internal combustion engine combined with high–energy-density fuels, as well as the strengths of electric systems combined with electrochemical batteries:

The tables below support the view expressed by Carlos Tavares - former CEO of Stellantis - who stated in 2023: “There were solutions that, from an environmental standpoint, were far more effective, less costly for consumers, less costly for public finances, and these solutions, for reasons that I would describe as dogmatism, were not treated with the necessary objectivity.”

The following tables show the average cradle-to-grave CO2 emissions (Life Cycle Assessment) of different powertrains and energy sources:

We observe that electric vehicles are unbeatable in terms of CO2 emissions in countries where electricity is heavily decarbonized, such as France thanks to its nuclear fleet. This is also the case in Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway, where 99% of electricity comes from unique hydropower resources.

However, on a global average, producing 1 kWh of electricity still emits around 460 g of CO2. It is therefore impossible to decarbonize the global automotive sector by relying solely on the performance of the few wealthy countries with low-carbon electricity. A strategy applicable at the planetary scale is needed: greenhouse gases have no borders.

Rich countries already struggle to impose electric vehicles. For poorer countries, the transition will take much longer, as EVs will only make sense once they have developed sufficient low-carbon electricity generation and reached a standard of living that makes this strategy feasible.

In this context, the internal combustion engine has a key global role to play, in combination with targeted electrification and with carbon-neutral fuels, whether organic or synthetic (e-fuels), which are compatible with fossil fuels and can be used anywhere in the world.

E-fuels represent a major long-term asset, enabling a gradual and sustainable global decarbonization - an opportunity that only the combustion engine is capable of fully leveraging.

E-fuels produced from low-carbon electricity have low life-cycle CO2 emissions and can be used in affordable, versatile vehicles that meet all mobility requirements. Beyond reducing emissions, they provide concrete answers to major energy challenges:

This is why abandoning the internal combustion engine would mean giving up decisive opportunities for the future. On the contrary, its improvement must be accelerated: it still powers more than 85% of new vehicles sold worldwide, remains central to the automotive industry’s assets, expertise, and know-how, and offers substantial room for progress.

We already know how to produce synthetic fuels, known as e-fuels, from low-carbon electricity, water, and CO2 captured from ambient air. These e-fuels are carbon neutral and do not contribute to climate change. Their cost could fall below €1/L by 2050 (Sources: Sunfire GmbH, Potsdam Institute). When used wisely, e-fuels could work alongside electrochemical batteries to manage electrical resources as efficiently as possible.

Both e-fuels and electrochemical batteries store electrical energy. E-fuels offer a lower “power plant to wheel” efficiency, but they store energy at atmospheric pressure in a virtually cost-free tank and at an energy density 70 times higher than that of batteries. These qualities are essential for mobile applications (transport). E-fuels are converted into motion by an internal combustion engine, which - together with its tank - forms a lightweight system.

E-fuels could become a key balancing tool in the energy transition, supporting grid regulation, long-term energy storage, and transport. They could also make the transition more socio-economically acceptable and meet the needs of users and regions where 100% electric mobility is not feasible.

Used in plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) or in extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs), e-fuels could in the future cover most trips longer than 80 km, which account for around 30% of total mileage in Europe (Source: NTS/RAND and ITC analyses).

Electrochemical batteries will remain ideal for daily travel and for the first 80 to 100 km of long journeys. This “PHEV or EREV + e-fuels” strategy is attractive to users and could lead to carbon-neutral mobility by 2050, without shocks or economic and industrial disruption.

The diagram below schematically illustrates what the path to carbon neutrality by 2050 could look like by combining the strengths of electrochemical batteries with those of e-fuels:

This chart is likely pessimistic, because the amount of electrical energy delivered through batteries rather than e-fuels could be significantly higher:

As an alternative to 100% electric mobility, EREVs using e-fuels could deliver massive savings. This deserves some quantified explanations:

Let us take a country like France, where 45 million vehicles (passenger cars + light commercial vehicles) travel a total of 540 billion kilometers per year. If all these vehicles were 100% electric, with an average consumption of 20 kWh/100 km including transmission, distribution, and charging losses, they would consume 108 TWh per year - the equivalent of 20% of the electricity produced by France in 2024 (536.5 TWh).

Now assume that instead of being 100% electric, these 45 million vehicles were e-fuel EREVs equipped with 25 kWh of batteries, instead of the 67 kWh carried on average by a 100% electric car sold in Europe in 2024.

Let us take the median production cost of EV batteries which, in 2025, is around €100/kWh. We will conservatively keep this €100/kWh figure, since it is not yet clear whether this price will fall with future volumes or, on the contrary, rise due to mining pressure and a reduction in Chinese overcapacity that currently pushes prices down artificially.

Let us assume that the average production cost of a combustion-engine range extender is €1,500, which is realistic.

The average saving per vehicle from reducing battery capacity would therefore be ([67 – 25] × 100) – 1,500 = €2,700, range extender included. If vehicle lifetime is 15 years, total savings would amount to 45 million × €2,700 = €54 billion every 15 years, while making cars cheaper and more affordable.

On top of these battery savings comes the saving on the public charging network. The cost of such a network in France can be estimated at around €100 billion, excluding annual maintenance costs. This figure corresponds to one charger installed for every 10 vehicles, in line with the recommendation of European Directive 2014/94/EU: that is, 4.5 million chargers, multiplied by an average installed cost of €22,000 per charger. This investment must be partially renewed every 20 to 30 years, the typical lifetime of charging stations.

Compared with the “100% electric” scenario, if in the “100% EREV” scenario 25% of mileage were covered using e-fuels, France would need to produce about 54 TWh of additional electricity. This corresponds to just under five EPR2-type nuclear reactors dedicated to e-fuel production, representing an investment of roughly €50 billion.

An EPR2 can operate for 80 years, during which time the French car fleet will have been renewed 80 / 15 ≈ 5.3 times. Compared with the “100% electric” scenario, the “100% EREV” strategy would save French consumers 5.3 × €54 billion = €286 billion, plus €100 billion in charging infrastructure at least twice over - i.e. more than €500 billion. From this total, we must subtract the investments required for e-fuel production infrastructure, on the order of €50 billion.

The overall savings over 80 years would thus be around €450 billion for a country like France - not counting the industrial and sovereignty benefits, which are vital for our economy.

Strategic advantages of combining PHEVs or EREVs with e-fuels:

The main drawback of e-fuels compared with electrochemical batteries is their power-plant-to-wheel efficiency. For the same distance traveled, producing e-fuels currently requires up to five times more electricity than using batteries. This ratio could drop to three or even lower by improving the efficiency of combustion engines, vehicles, and e-fuel production.

However, this drawback would be largely offset by the long-term advantages of e-fuels:

1. Energy production and flexibility

2. Distribution, use cases, and driving range

3. Industrial and sovereignty advantages

4. Climate outlook

This figure highlights Europe’s singular position: in 2023, 78% of all new vehicles sold worldwide were sold in countries that have not decided to ban the internal combustion engine (ICE):

Within Europe itself, there are strong disparities in electrification levels depending on national wealth. Electric vehicles (EVs) gain market share primarily in countries with a high GDP per capita: in the first half of 2025, just three countries - Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium - accounted for 62% of all EV sales in the EU-27.

The typical electric-car buyer is a wealthy individual living in a wealthy country. In most cases, this person receives government support to purchase an EV. This subsidy is funded by all taxpayers, both rich and poor. To address this inequity, France introduced a “social leasing” scheme, enabling 50,000 low-income households each year to rent an electric car for €140 to €200 per month for at least three years. This subsidized rent comes in addition to a €7,000 purchase incentive, also paid by taxpayers.

In Norway, the fourth-richest country in the world with a per-capita income of USD 90,434, nearly 95% of newly registered cars are now electric. The incentives for buying EVs, combined with strong disincentives for combustion-engine vehicles, are such that electric cars are significantly cheaper to buy and to operate than thermal vehicles. Norway can afford these ambitious electrification policies thanks to its oil and gas revenues: it owns the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund - €1.75 trillion in assets - financed by petroleum and gas extraction. This fund, initially called the “Government Petroleum Fund,” was renamed in 2006 the “Government Pension Fund Global.”

Yet these islands of wealth - Europe and Norway, with a combined annual market of under 130,000 cars - will not decarbonize the world on their own. Together they represent only 5% of the global population, and if they reduce their oil-related CO2 emissions while less-developed countries increase theirs, the net effect on the climate will be zero.

This is why the internal combustion engine has a decisive role to play in the decades ahead, at the global scale: it remains accessible to populations worldwide, it adapts to all usage conditions, and it represents a major opportunity for decarbonization through improvements in efficiency and through the reduction of the climate impact of the fuels it consumes.

The gradual reduction of the carbon footprint of fuels, combined with the hybridization of vehicles (HEV, PHEV) and the deployment of high-efficiency combustion engines, is undoubtedly the key to transitioning step by step from today’s fossil-fuel-based world to one with a much lower climate impact. Range extenders will also likely become more common in electric vehicles (EREV, REEV), supporting their broader adoption. Under this logical and probable scenario, only Europeans and a few other populations around the world will be deprived of combustion engines, while the rest of the world produces more and more of them.

This is why, in 2022, Luca de Meo, then CEO of Renault, stated: “The combustion engine will remain a relatively stable business. It’s paradoxical, but the peak of global volumes is still ahead of us.”

Will Europe - the birthplace of the automobile and long-standing champion of the combustion engine - be able to stay in the race for exports? Nothing is less certain. To remain competitive in combustion technologies, even in export markets, Europe must continue innovating and maintaining its technological lead. A European factory that shuts down will not reopen, and its know-how will be irretrievably lost. Once you stop producing, you stop knowing how to do it - and progress stops. Yet European manufacturers have already dismantled much of their combustion-engine research capacity. They were forced to invest massively in electric technologies - still unprofitable for now - at the expense of combustion, since the latter is officially banned in Europe from 2035 onward.

These “electric” investments were imposed by an extremely restrictive CO2 -reduction timetable, combined with heavy penalties (CAFE regulation: €95 per gram of excess CO2). The schedule is so tight that only rapid, large-scale electrification of sales can prevent manufacturers from losing all their profits to penalties. This is why, at auto shows, they now showcase mainly electric cars; why their advertising focuses almost exclusively on EVs; and why dealerships offer discounts on electric models by leveraging government subsidies.

The problem: the market is not following at the expected pace.

Electric vehicles - “zero-emission” in name only - are too expensive, depreciate too quickly, and are difficult to resell. They are inconvenient to recharge, their range remains limited, and repairs are costly. Despite efforts to force Europeans to buy them by using taxpayer money to subsidize them, a glass ceiling is clearly visible: beyond early adopters and wealthy, committed environmentalists, the broader population simply cannot afford a genuine electric car at an astronomical price. And these same households are not rushing to buy lower-cost electric cars either, especially when those models barely resemble a proper vehicle, come with minimal equipment, and offer disappointing range.

This dismantling of Europe’s automotive industry is an extraordinary opportunity for China. Europeans are now buying Chinese batteries they will never be able to manufacture at the same cost, in order to produce electric vehicles that cannot compete with their Chinese equivalents. Once Europe’s automotive industry has collapsed, Europeans - at least those who can still afford a car - will end up driving Chinese hybrid vehicles equipped with Chinese combustion engines. European taxpayers will have bled themselves dry to destroy their own jobs, impoverish themselves, and subsidize Chinese factories.

This economic and social catastrophe is fertile ground for populism, unrest, and the relegation of environmental concerns to the very bottom of political priorities. Aware of this, several EU member states - most notably Italy, Germany and Poland - are pushing back against what they view as a suicidal timetable and technological straitjacket. They are negotiating deadline extensions, regulatory easing and greater technological flexibility with the European Commission.

All European cars account for just 0.8% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. That is very little. As a result, the impact of converting the entire European car fleet to full electric - a process that will take decades - on global warming will be small, and indeed almost invisible:

This modest environmental gain will, however, come at a heavy industrial, economic, and social cost, with disastrous consequences for European prosperity. Moreover, the climate benefit of an “all-electric” strategy is not weighed against other environmental risks. Mining pressure and the associated destruction of ecosystems - albeit far from our shores - are still not factored into the cost–benefit analysis of 100% electric mobility.

Let us calculate the greenhouse gas emission savings from an all-electric European car fleet:

In Europe, assuming that by 2040 the electricity generation mix will be more decarbonized than it is today, replacing a 100% combustion vehicle with a 100% electric vehicle would reduce CO2 emissions per kilometer by around 70% (source: Transport & Environment). Thus, converting the entire European car fleet to fully electric vehicles could reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by at most 0.56% (0.8% [all European cars] × 70%). This figure assumes that combustion engines make no progress - which is unrealistic - and that global GHG emissions do not increase, which is also unlikely.

In reality, this 0.56% reduction, achieved only after several decades, is all the more insignificant given that global greenhouse gas emissions have been rising by around 1.1% per year since 2000 and continue to do so. The only year in which global GHG emissions fell was during the COVID crisis, which clearly illustrates that economic activity and emissions go hand in hand:

However, these observations do not call into question the need to reduce the environmental footprint of automobiles, nor the need to move away from an all-oil system. The point here is to emphasize that the automotive sector - although highly visible to everyone - must not become the scapegoat for climate change to the extent that we overlook the contribution of far more influential sectors.

The automotive sector must contribute to global decarbonization in a proportionate, gradual, and economically sustainable manner. It must not become the instrument of extremist environmental policies imposed on the population without any serious prior impact assessment.

A final 0.56% reduction in global GHG emissions… but over what timeline, and with what guarantees?

Europe’s car fleet consists of roughly 280 million vehicles (passenger cars and light commercial vehicles). In 2024, fewer than 12.2 million new vehicles were registered in the EU27, compared with 14.7 million in 2019 - a 17% contraction of the market in just five years.

Assuming that all new cars sold in Europe were fully electric - which is still far from the case (BEVs: 13.6% market share in the EU27 in 2024) - it would take at least 23 years to renew the entire European fleet (280 ÷ 12).

Such a renewal relies on fragile assumptions:

If battery lifespan does not improve and the new-car market continues to contract, Europe’s car fleet will mechanically shrink to a new equilibrium of around 180 million vehicles (12 million annual sales × 15-year lifespan) - a 36% reduction. In such a scenario, a growing share of Europeans - starting with the most modest households - would lose access to personal mobility. Freedom of movement, a key pillar of Europeans’ quality of life, would be undermined. E-mobility leading to immobility: a genuine social time bomb.

Added to this is a major industrial and economic threat.

The European automotive industry, currently at risk, represents (source: ACEA):

Safeguarding the automotive sector - Europe’s main industrial pillar - requires defining decarbonization strategies that are coherent, technologically open, and based on a realistic timeline.

If not, Europe’s decarbonization will stem primarily from its deindustrialization, the loss of mobility among its population, and a general impoverishment. Europe would enter a state of economic decline - the most effective lever for reducing emissions.

The link between poverty and low CO2 emissions is obvious. Take Burundi, for example. With a GDP per capita of 154 dollars, annual per-capita CO2 -equivalent emissions are only 0.06 tons. By comparison, a German emits 14 tons of CO2 equivalent per year (233 times more) for a GDP per capita of 55,800 dollars (362 times higher). Will Europeans agree to sacrifice their standard of living on the altar of decarbonization - to endure unemployment, poverty, social tensions, and violence? To avoid this, other strategies could be implemented, more acceptable to the population and ultimately more effective from an environmental standpoint

In this context, the high-efficiency combustion engine has a decisive role to play, alongside the reduction of fuel carbon intensity and in combination with electrification and hybridization. Improving it has global impact, offering European manufacturers a strategic advantage and significant economic opportunities.

Finally, the trillions of euros required for the full electrification of Europe’s automotive fleet must not undermine our ability to invest in sectors that are easier to decarbonize, such as buildings, industry, and electricity generation. These stationary sources - technically simpler to address - account for nearly two-thirds of global GHG emissions, i.e. ten times more than all cars worldwide.

The following table shows that, in Europe, replacing fossil-fuel power plants (coal, gas, oil) with nuclear power stations would be far more effective than replacing combustion-engine cars with battery electric vehicles - at a cost per ton of CO2 avoided up to ten times lower: