Few strategies can still significantly improve the efficiency of modern gasoline engines, which are already considered “state-of-the-art.” In this context, turbulent jet ignition (TJI) offers the strongest potential to reduce fuel consumption at low cost and with limited investment.

The capabilities of TJI have been evaluated many times through R&D programs conducted by various OEMs, research institutions, and suppliers, including Mahle (Mahle Jet Ignition [MJI]), Renault (GASON, EAGLE), IAV (passive and active PCSP), FEV, Ford, FVV (ICE2025+, SACI), GAC, and Honda.

To this, we can add the results obtained with Valvijet, an enabler that allows TJI to drastically reduce fuel consumption over the WLTP cycle as well as in real-world driving conditions - where the true challenge of pre-chamber ignition lies.

Indeed, with TJI, peak efficiency is too often showcased as an achievement, whereas what truly matters is average efficiency in real-world use and over homologation cycles.

The following table positions the energy and economic profitability of TJI implemented with Valvijet, whose manufacturing cost has been the subject of a detailed study conducted with leading industrial partners:

As shown in this table, compared with a modern GDI turbo VVT engine, TJI implemented with Valvijet delivers a major reduction in fuel consumption, and does so at the lowest cost per gram of CO2 avoided. When combined with a 48-V mild-hybrid system, Valvijet can even match the fuel-consumption reduction of a full-hybrid system while offering a manufacturing cost increase that is only half as high.

The theoretical potential of TJI is well known. The question is no longer “how much” TJI can reduce CO2 emissions - we already know that - but rather “how” to deliver an operational TJI system with no functional or technological blockers, one that can be industrialized and commercialized in the near term.

Providing the technological package required to answer this question is precisely the purpose of Valvijet.

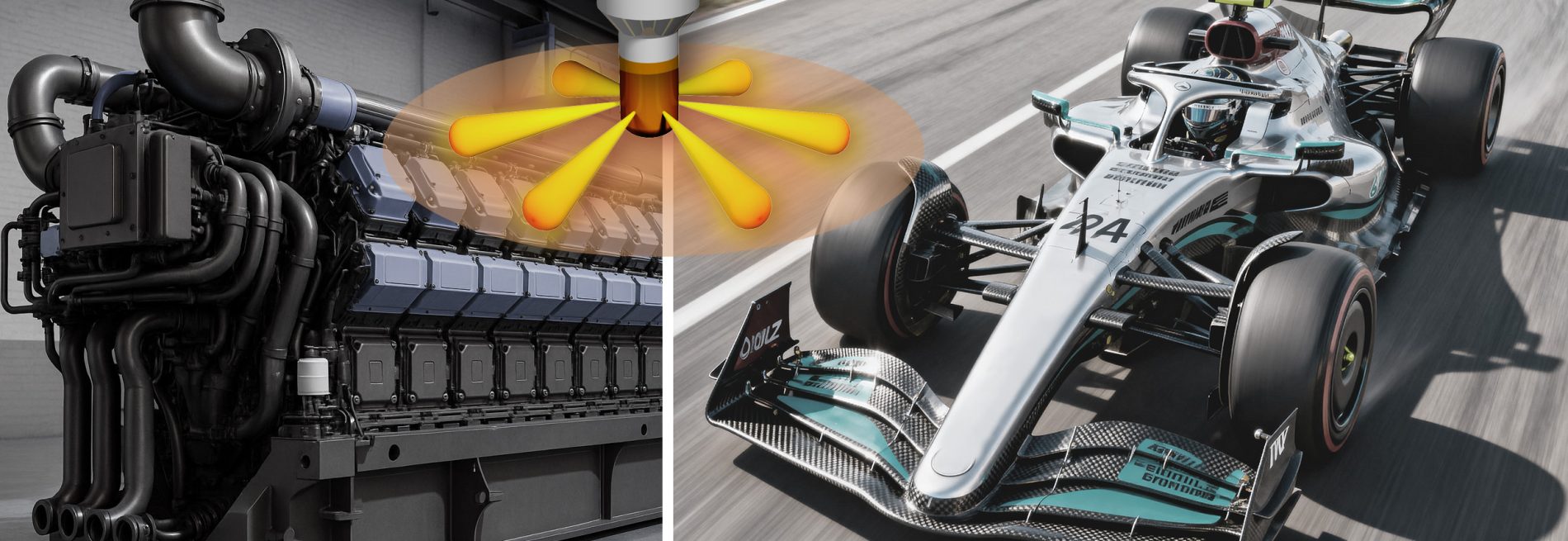

The first pre-chamber ignition engine concepts date back to the early 20th century. Pre-chamber ignition consists in shaping a small cavity - a pre-chamber - in the cylinder head, connected to the main combustion chamber through a set of orifices in a pre-chamber nozzle (see diagram below).

The pre-chamber contains a fuel-air mixture: the “pilot charge.”

This pilot charge is ignited by a spark plug. As it burns, it emits flame jets into the engine’s main combustion chamber through the orifices. These jets - known as “turbulent jets” or “ignition torches” - ignite the main charge:

When properly implemented, pre-chamber ignition offers major advantages:

These unique characteristics open the door to new possibilities:

The following diagram shows the origin of the TJI gains induced by the Miller + EGR combination:

In theory, pre-chambers are therefore highly advantageous. Despite this, with a few exceptions, only large gas engines have been equipped with them since the 1960s, and Formula 1 engines since 2014 - which enabled them to exceed 50% brake thermal efficiency:

One cannot discuss pre-chambers without mentioning the CVCC engine, produced from 1973 to 1985. At the time, the CVCC allowed Honda to meet U.S. emissions regulations without a three-way catalyst. Operating with a lean mixture, this engine was compatible with both leaded and unleaded gasoline. It opened the U.S. market to Honda.

In 2020, TJI returned to the automotive sector with the “Nettuno” engine of the Maserati MC20, a car produced in only 260 units in 2024. The Nettuno engine is equipped with a passive pre-chamber. One of Maserati’s objectives is to avoid over-rich operation at full load, which is now prohibited due to excessive pollutant emissions.

On October 28, 2025, Stellantis - the parent company of Maserati and Jeep - officially introduced the Hurricane4 Turbo. This 2.0-L, 4-cylinder engine, delivering 324 hp (120 kW/L), will equip the 2026 Jeep Grand Cherokee. Like Maserati’s Nettuno, the Hurricane4 features two spark plugs per cylinder, one of which sits in a passive pre-chamber.

The Hurricane4 Turbo includes direct injection, port injection, and a variable-geometry turbocharger with a wastegate. It operates in Miller cycle thanks to an electric cam phaser and also incorporates a variable-displacement oil pump and an electric water pump.

This particularly rich technology mix allows the Hurricane4 to reach a peak efficiency of 40%, an excellent value. Its efficiency varies little with power once above approximately 20 kW.

The Hurricane4 Turbo is a remarkable “premium” achievement that brings together the best technologies available today, similar to the Volkswagen 1.5 L EVO engine. Its dual ignition system allows it to cover all operating situations: when the pre-chamber is ineffective, the spark plug takes over (low loads, catalyst heating, cold start). When the passive pre-chamber performs best, it becomes the primary ignition source (Miller cycle, high loads). There are also conditions in which both ignition systems work cooperatively.

However, the Hurricane4 Turbo does not use external EGR, even though this strategy is essential to significantly increase efficiency at low loads - the most frequent operating conditions in real-world driving. External EGR is, in fact, not compatible with passive pre-chambers.

Another notable example is the V12 engine of the Zenvo Automotive hypercar (planned for 100 units), the only engine equipped with an active pre-chamber, developed by Mahle Powertrain England.

Looking ahead, the company Horse recently presented a powertrain that can be integrated into electric vehicles: the “Future Hybrid Concept.” This powertrain includes an engine with a passive pre-chamber and claims improved capability to burn different fuels. Supplier Mahle has also developed a range extender based on the same principle. These engines, however, are not yet in production.

Despite the promise of TJI, which has been studied for more than 100 years, no engine relying solely on a pre-chamber has yet reached high-volume automotive production: major technological roadblocks still prevent it. A true breakthrough is needed to make pre-chamber ignition a genuinely mainstream technology.

Valvijet is undoubtedly the long-awaited breakthrough required to bring TJI into mass automotive production and to address low-load operation - where fuel-consumption reduction truly matters.

To understand the challenges of TJI, it is necessary to analyze its different implementation variants, from the simplest to the most sophisticated, which are presented schematically below:

1 – Passive pre-chamber:

This is the simplest configuration. It consists of surrounding the spark plug with a cap drilled with orifices. This cap is sometimes integrated directly into the spark plug. From an industrial standpoint, it presents no particular difficulty.

The air–fuel mixture is supplied to the pre-chamber from the main chamber during compression. The main chamber and the pre-chamber form an acoustic system, which is why passive pre-chambers are mainly used in engines operating over a narrow range of speed and load.

The ignition effectiveness of passive pre-chambers is limited by residual burnt gases (RBG), especially at low loads, where most of the fuel is consumed in the WLTP cycle or in real driving conditions (RDE). These “fatal” RBG, which already impose a strong constraint on passive pre-chamber ignition, severely limit - or even eliminate - the possibility of intentionally diluting the main charge with I-EGR (internal) or E-EGR (external cooled).

Low loads:

The passive pre-chamber forms a “dead end” or “dead volume” from which residual burnt gases (RBG) are difficult to evacuate between cycles. The absolute amount of RBG trapped in the pre-chamber varies little with load. Thus, the lower the engine load, the less fresh mixture is introduced into the cylinder, and the higher the relative proportion of RBG in the pre-chamber becomes, regardless of its volume.

At the loads most represented in WLTP/RDE cycles - where the majority of the fuel is burned - the RBG content in the pre-chamber can reach 30 to 40%, or even more. Such levels make the pre-chamber unstable and ineffective. It then becomes necessary to install a second spark plug to take over, as implemented in the Stellantis Nettuno and Hurricane4 engines.

The benefit of a passive pre-chamber is limited on WLTP/RDE. It can, however, offer certain indirect advantages for highly loaded and downsized engines, such as enabling a higher compression ratio or avoiding the over-rich operation that is now prohibited by regulation. This advantage, however, concerns high-performance vehicles rather than mainstream cars - the main contributors to corporate CO2 emissions (CAFE).

EGR dilution (intentional EGR):

Diluting the engine with EGR is beneficial for de-throttling (reducing pumping losses), decreasing thermal losses to the walls, and reducing knock sensitivity at high loads. However, high-load operation occurs only rarely - mainly during transients, on inclines, or in sporty driving.

De-throttling the engine and reducing its thermal losses is the most effective strategy to lower fuel consumption in WLTP/RDE. Yet passive pre-chambers, which already struggle to provide stable ignition at low loads, perform even worse when additional EGR is introduced into the main charge.

Indeed, diluting the main charge with EGR also dilutes the pilot charge introduced into the pre-chamber in the same proportion. This added EGR combines with the residual burnt gases (RBG) already trapped inside the pre-chamber. Cycle-to-cycle dispersion then increases significantly: in the pre-chamber, fast combustions alternate with slow combustions, and vice versa. The main combustion chamber inherits these instabilities and amplifies them.

Furthermore, ignition becomes less effective: the more diluted the pilot charge, the weaker and cooler the turbulent jets become.

This is why, at low loads (WLTP/RDE), the efficiency benefit of passive pre-chambers is modest, null, or even negative compared with conventional spark ignition.

Another limitation: passive pre-chambers make cold starts problematic. During filling from the main chamber, part of the vaporized fuel condenses while passing through still-cold orifices, or upon contact with the cold internal walls. Deprived of part of the fuel it should contain, the mixture in the pre-chamber becomes too lean to ignite.

To address this issue, an obvious solution is to install - as Stellantis has done - a second spark plug in the main chamber, which also serves other functions. Another option would be to preheat the pre-chamber using an electrical device, but this would increase cost and complexity relative to the limited CO2 benefit, and would introduce a preheating delay before starting - difficult to accept.

A further drawback of passive pre-chambers is their poor catalyst-heating capability. Once again, the second spark plug allows the system to revert to more traditional operation. However, by acting as a hydrocarbon trap, the passive pre-chamber makes compliance with emissions standards more challenging.

Catalyst heating becomes less critical when the engine works in combination with sufficiently powerful electrified systems (hybridization). Another alternative is to equip the vehicle with an electrically heated catalyst (EHC). The issue: its added cost is high relative to the modest CO2 reduction enabled by passive pre-chambers.

For all these reasons, despite their simplicity and more than a century of research, passive pre-chambers have never found their place in mainstream automotive applications. Implemented in heavily hybridized powertrains, they may provide a few percentage points of peak-efficiency improvement for an internal combustion engine - but this remains a stopgap solution. Storing and releasing mechanical energy through batteries involves a cascade of efficiency losses. Nothing matches the efficiency of a combustion engine that avoids this intermediate storage and drives the wheels directly through a gearbox.

2 – Active pre-chamber “fuel injection only:

This configuration is suitable for engines operating with lean or even ultra-lean mixtures, in practice up to λ > 2. The pre-chamber is supplied, as in the case of passive pre-chambers, with a fuel–air mixture coming from the main combustion chamber. Since the main charge is fuel-lean and oxygen-rich, an injector located in the pre-chamber enriches the pilot charge with fuel so that it regains normal combustion stability and temperature. This maximizes ignition efficiency, notably by releasing into the main chamber chemical species that are particularly reactive in the presence of OH radicals, such as carbon monoxide.

However, atomizing and vaporizing gasoline in a very short time within the highly constrained volume of a pre-chamber represents a real challenge. The walls retain a significant share of the fuel due to wall-wetting effects. This makes controlling the effective richness of the pilot charge uncertain and leads to substantial particulate emissions, requiring the installation of a particulate filter in the exhaust system.

The main drawback of “fuel-injection-only” active pre-chambers is that they apply only to engines operating with excess air. This type of engine - known as “lean burn” - is increasingly being phased out in the automotive sector because of the cost and complexity of NOx aftertreatment in an oxidizing environment.

Indeed, the three-way catalyst - the most economical pollutant aftertreatment device - does not reduce nitrogen oxides in the presence of free oxygen.

Selective catalytic reduction (SCR), used in diesel engines, can reduce NOx. However, SCR is costly to manufacture and maintain, bulky to the point of creating integration issues in small vehicles, and constraining for drivers. This system operates using a urea solution known commercially as “AdBlue”. Moreover, the Euro 6d regulation now requires SCR to operate 100% of the time. There are no longer off-cycle operating points during which SCR can be deactivated.

As a result, the vehicle must be refilled with AdBlue more frequently, sometimes several times within 20,000 km. If AdBlue runs out completely, the vehicle may lose power or even fail to restart.

To be more direct: in automotive applications, replacing a diesel engine with a lean-burn engine using a “fuel-injection-only” active pre-chamber makes no sense. The result would be similar efficiency, similar cost, and similar aftertreatment constraints. One might as well produce diesel engines.

3 – Active pre-chamber with “air/fuel injection”:

This configuration is the only one that avoids both the limitations of passive pre-chambers - simple but not very efficient - and the lack of relevance of “fuel-injection-only” active pre-chambers, which are restricted to lean mixtures and offer no advantage compared with diesel engines.

Injecting an air–fuel mixture into the pre-chamber makes it possible to maintain a stoichiometric main charge (λ = 1). The main charge is then diluted only with non-reactive, oxygen-free exhaust gas recirculation (EGR). Remaining at stoichiometry is essential to treat nitrogen oxides using a simple and cost-effective three-way catalyst.

Because the main charge is stoichiometric but heavily diluted with EGR, injecting fuel alone into the pre-chamber is not sufficient to restore normal combustion there: air must also be injected. Injecting only gasoline into the pre-chamber would have no effect, as the corresponding oxygen required for its combustion would be missing.

In practice, the energy of the pilot charge represents between 1.5% and 4% of the total cycle energy. The more the main charge is diluted with EGR, the greater the ignition energy - and therefore the pilot charge - must be. The ideal air–fuel ratio of the pilot charge is about 11.3:1, corresponding to an equivalence ratio φ = 1.3 or a lambda λ = 0.77.

A fuel-rich pilot charge generates a high flame speed in the pre-chamber and produces numerous reactive intermediates (H, O, OH, CH, CO, H₂, C1–C2 radicals). These species are carried into the turbulent jets and promote the combustion of the highly EGR-diluted main charge. This enables fast and homogeneous combustion of the main charge, with low knock sensitivity, across a wide EGR operating range.

However, injecting air and fuel simultaneously into the pre-chamber poses a significant challenge.

It is indeed necessary to:

These conditions are essential for stoichiometric active-pre-chamber engines that are compatible with three-way catalysts, whose main charge is heavily diluted with EGR, and that deliver high efficiency across their entire operating range. If these conditions are not met, high-efficiency TJI under real-world driving conditions will remain a laboratory concept with no industrial prospects.

Remaining compatible with three-way catalysis is crucial. Despite the sharp rise in PGM (platinum-group metal) prices over the past decade, the three-way catalyst remains cost-effective: its manufacturing cost is between €220 and €400, compared with €700 to €1,200 for a lean-burn aftertreatment system (diesel or lean-gasoline), which also entails additional operating costs and constraints (SCR).

Another advantage of the active pre-chamber for a “lambda 1” engine is that gasoline direct injection (GDI) is no longer required. Replacing GDI with multipoint port fuel injection (MPFI) offers two major benefits:

These cost reductions significantly enhance the economic performance of TJI, expressed in €/g CO2/km avoided relative to state-of-the-art turbocharged GDI engines. Compared with less advanced engines, the cost/benefit ratio changes little: manufacturing savings are smaller, but CO2 reduction is greater.

The fact remains that the technologies capable of delivering all the required functions do not yet exist - except in the case of Valvijet. These functions include the preparation and injection, within the pre-chamber, of a precise and homogeneous fuel–air mixture, based on several strategies illustrated in the following diagrams:

The advantages and disadvantages of these strategies are presented below.

Variant No. 1:

Variant No. 1 consists in injecting air (A) and fuel (F) using two independent injectors, each opening directly into the pre-chamber. This approach has been tested by Ford, FEV, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The claimed fuel consumption reduction is 23% on a 3.5-L Ford F-150 “EcoBoost” V6 pickup, although this reduction cannot be attributed solely to TJI: other factors also contribute.

This architecture raises several issues.

First, to form a homogeneous, fully gaseous air–fuel mixture, it is extremely difficult to atomize and vaporize gasoline into compressed air injected simultaneously into the confined volume of a pre-chamber. All of this must occur in an extremely short time - within just a few crank-angle degrees. Under such conditions, achieving good mixture homogeneity within the pre-chamber is difficult, if not impossible, and some of the liquid fuel will inevitably wet the walls. This leads to a leaner pilot charge and generates particulates.

This triggers a vicious cycle: wall wetting forces an increase in fuel injection to restore the richness of the gaseous mixture, but injecting more fuel reduces the fuel’s ability to evaporate, which in turn increases wall wetting.

Controlling the composition of the pilot charge becomes even more difficult in transient conditions: changes in the composition of the main charge also affect the pilot charge, and the evolving thermal state of the pre-chamber further shifts the mixture composition.

Another issue with Variant No. 1 is packaging: placing two injectors plus a spark plug in each cylinder severely constrains cylinder head architecture and complicates cooling. Under these conditions, designing a small-volume pre-chamber (< 1 cm³) with low internal surface area becomes difficult. Yet if the pre-chamber is too large, the consumption of compressed air becomes excessive, harming engine efficiency.

Moreover, the energy released in the pre-chamber becomes unnecessarily high, and the increased internal surface area promotes heat losses, which reduce efficiency.

The goal, on the contrary, is to design the smallest possible pre-chamber in order to minimize the required pilot charge, reduce the amount of residual burned gas, and limit thermal losses. The problem is that a compact pre-chamber does not offer enough space to accommodate two injectors and promotes wall wetting.

Another drawback of Variant No. 1 is that it requires high-pressure direct gasoline injection inside the pre-chamber, at a cost equivalent to that of the main direct-injection system. Yet TJI is advantageous precisely because it replaces GDI and allows engines to revert to the less expensive and far less particle-emissive PFI solution.

Such a configuration is unlikely to reach industrial deployment.

Variant No. 2:

This concept is similar to the “air-assist injection” system developed by Orbital Engine (Orbital Combustion Process) in the early 1980s. In this case, air-assisted injection of compressed air is applied to an ignition pre-chamber.

Ford, FEV, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, as well as several renowned engineering firms, have studied this variant, which provides solutions to several issues raised by Variant No. 1.

Variant No. 2 also includes two injectors: a fuel injector (F) and a mixture injector (A/F). The fuel injector (F) opens into a “mixing chamber,” where it forms an air–fuel mixture thanks to a supply of compressed air (A). Once formed, this mixture is introduced into the pre-chamber through the mixture injector (A/F).

As with Variant No. 1, the confined volume in which the air–fuel mixture is formed remains a major challenge. A mixture as homogeneous as possible must be created, with minimal fuel impingement on the walls so that no liquid fuel reaches the pre-chamber. The time available to achieve a homogeneous gaseous mixture is extremely short - at best only a few milliseconds at high engine speed.

In the mixing chamber, the gasoline is atomized into fine droplets and must evaporate into the compressed air while maintaining minimal mixture-richness heterogeneity. A small amount of liquid fuel may nevertheless reach the internal wall of the pre-chamber as it exits the second injector (A/F), but in proportions vastly lower than in Variant No. 1 - roughly twenty times less, in order of magnitude.

This configuration has the advantage of maintaining a low fuel mass inventory in the pre-chamber supply line. However, like Variant No. 1, it shares the drawback of requiring high-pressure gasoline injection into the mixing chamber, even though TJI advantageously replaces GDI and allows engines to be refitted with PFI, which is less expensive and far less particulate-emissive.

Limits common to Variants No. 1 and No. 2 – calibration:

Variants No. 1 and No. 2 present several engine-calibration challenges.

Calibrating the engine requires full control of the initial conditions inside the pre-chamber at the start of each cycle. The progression of combustion in the main chamber depends directly on these conditions. Among them are the amount of energy introduced, the level of residual burned gases, overall mixture richness, richness homogeneity, turbulence at the moment the pilot charge is ignited by the spark plug, and temperature.

However, with Variants No. 1 and No. 2, controlling the richness of the pilot charge introduced into the pre-chamber requires precise knowledge of the mass flow rate of the air injector and that of the fuel injector. This would require extremely high-precision, wide-range metrology capable of measuring the flow of each injector - something that is practically and economically impossible.

In addition to controlling the individual flow rates of the air and fuel injectors, one would also need to know the amount of liquid fuel present on the internal walls of the pre-chamber, both in steady-state and transient operation. This point is less critical in the case of Variant No. 2.

Determining the individual flow rates of the pre-chamber air and fuel injectors using lambda-sensor feedback is equally impossible: in such feedback systems, the main injector alone accounts for up to 98% of the energy supplied. Therefore, total-richness corrections required for proper three-way catalyst operation will continue to be applied through adjustments to the main injector’s flow rate, without accurate knowledge of the pre-chamber injectors’ flow rates (STFT/LTFT corrections).

It is therefore difficult to calibrate a “lambda 1” engine equipped with a pre-chamber fuel-mixture supply system corresponding to Variants No. 1 or No. 2.

Variant No. 3:

This variant, developed by Valvijet, solves the problems associated with Variants No. 1 and No. 2:

Variant No. 3 “Valvijet” incorporates an intelligent proportional injector equipped with a position sensor (Z).

This variant includes an air–fuel mixer that supplies the pilot charge to the engine’s pre-chambers. The mixer consists of a mixing chamber of about 45 cm³ into which compressed air (A) and fuel (F) are introduced in precisely controlled proportions (±2%). A turbine rotates continuously inside this chamber: it homogenizes the air–fuel mixture and dries the internal walls. The chamber contains the equivalent of one second of full-power consumption (150-kW engine), and up to one and a half minutes at idle.

The mixture is injected into the pre-chamber by an injector (A/F) with continuously variable needle lift. The instantaneous needle position is measured by the high-bandwidth position sensor (Z).

This Variant No. 3 does not require one high-pressure gasoline injector per cylinder, but only a single (A/F) pilot charge injector per cylinder: the production of the fuel mixture is centralized in an A/F mixer shared by all cylinders.

The advantages of this configuration are numerous:

Variant No. 4:

Variant No. 4 is essentially Variant No. 3 with the addition of a Valvijet magnetically actuated check valve, located in the tip of the pre-chamber as well as at the outlets of the turbulent-jet orifices. When the valve is closed, the pre-chamber is isolated from the main chamber. When it is open, gases can flow from the pre-chamber to the main chamber through the turbulent-jet orifices.

The valve recloses under the combined action of a magnetic field and the pressure difference between the pre-chamber and the main chamber.

This variant ensures stable and repeatable initial conditions in the pre-chamber at the beginning of every cycle.

Indeed, without a check valve, the initial conditions inside the pre-chamber depend partly on the composition of the main charge. In particular, the amount of residual burned gases (RBG) in the main charge - consisting of internal or external EGR - directly influences the amount present in the pre-chamber. Yet residual burned gases are a true “poison” for pre-chamber-based ignition:

Working together with the “intelligent” A/F injector, the Valvijet check valve ensures a pilot charge with “near-zero RBG.” To achieve this, a scavenging injection - representing about 10% of the total pilot charge - is performed before the pre-chamber filling injection, at low pressure, at the very beginning of the intake stroke. As a result, the pilot charge trapped in the pre-chamber no longer comes partly from the A/F injector and partly from the main charge. Thanks to the valve, the pilot charge comes exclusively from the A/F injector.

Another advantage of the valve is the ability to control the combustion speed of the pilot charge. This speed depends not only on the level of residual burned gases (RBG) - which, thanks to the valve, is close to zero - but also on the turbulence inside the pre-chamber at the moment the spark is generated between the plug electrodes. With the Valvijet intelligent proportional injector, this turbulence can be precisely tuned through an optimized needle-lift profile and by adjusting the overlap between the spark event and the end of injection.

Because the valve isolates the pre-chamber, turbulence can be finely adjusted without interference from gases originating in the main charge entering through the turbulent-jet orifices.

The absence of RBG in the pilot charge and the control of its combustion speed within the pre-chamber ensure reliable ignition at low and very low loads - those most prevalent in WLTP cycles and real-world driving.

The benefits of the valve do not stop there:

With the valve, pilot-charge injection takes place in a closed volume, kept at low pressure regardless of engine load. Flow through the injector needle remains sonic throughout the filling phase. This maximizes flow for a given needle lift, reduces the required needle lift, and enables precise control of the quantity of gaseous mixture injected into the pre-chamber.

Because the pre-chamber volume is sealed, the amount of energy contained in the pilot charge is chosen rather than imposed: gases from the main charge cannot enter the pre-chamber. This closed space allows the pilot-charge injector supply pressure to be reduced, lowers the compression energy required, and - critically - keeps the mixture below the partial-fuel-recondensation threshold, regardless of engine temperature.

This characteristic is decisive for cold starts, which represent one of the major challenges of pre-chamber ignition systems. Thanks to the valve, it is possible to introduce all the necessary energy, even at –30 °C, to meet ignition requirements up to about 12 bar BMEP - potentially more with a Miller cycle - without risking fuel recondensation in the feed circuit (between the mixer and the pre-chamber) or inside the pre-chamber itself.

Indeed, the pressure at the end of pre-chamber filling is controlled via the quantity of mixture injected. Except in very specific cases, this pressure always remains below that of the main chamber. This reduces gas density between the spark-plug electrodes and helps preserve the plug: spark-plug durability is among the critical challenges of pre-chamber ignition systems.

Indeed, the valve protects the spark plug: breakdown voltage is low because pre-chamber pressure is limited by the valve. The absence of RBG allows the spark-plug gap and ignition energy requirement to be reduced even further. The slightly rich mixture making up the pilot charge has better ignitability. This reduces stress on the insulator and on the high-voltage cables, and makes it possible to shorten discharge duration. A small-diameter spark plug (e.g., 8 mm) can therefore be used - its durability is preserved and it is compatible with a small-volume pre-chamber (e.g., 0.7 cm³).

Since the sealed volume of the valved pre-chamber is no longer affected by what occurs in the main combustion chamber, it becomes possible to greatly widen the ignition phasing window while maintaining excellent combustion stability (COV). This is crucial for controlling engine torque on a cycle-by-cycle basis during transients, via spark-timing retard and temporary efficiency degradation, just as is done with a conventional spark plug - and even by momentarily cutting a cylinder. This point is essential: torque control by spark advance, difficult with conventional pre-chambers, is indispensable for calibrating an automotive engine.

Late ignition is also indispensable for heating the three-way catalyst during cold starts. The objective is to generate high exhaust temperatures, with the throttle wide open, without exceeding a BMEP only slightly above motored levels. Late ignition is delicate with a pre-chamber: it must be accompanied by fine adjustment of the air–fuel mixture quantity forming the pilot charge. Too much ignition energy “blows out” the nascent flame in the main chamber; too little fails to initiate combustion. Moreover, to maximize catalyst heating while minimizing work delivered to the piston, combustion must be slow. The Valvijet tandem - intelligent proportional injector + valve - allows precisely these adjustments and achieves the expected results.

Variant No. 4, as implemented by Valvijet technology, provides all the features and all the control levers required to achieve a high-performance, fully controllable, high-efficiency stoichiometric TJI engine.